What Is Cybersquatting? What to Know & How to Prevent It

Between January and October 2020, the World Intellectual Property Organization handled 3,405 cases of cybersquatting. Here’s what to know about cybersquatting

You’ve spent years and a lot of money building your business’s brand. But what if I told you that someone could erase a lot of that progress by buying a $10 domain that looks similar to yours? And to make matters worse, what if they threaten to ruin your brand name if you don’t agree to buy the imposter domain from them? This scenario describes a tactic known as cybersquatting.

But what is cybersquatting and how can you protect your organization from it? In this article, we’ll cover:

- What cybersquatting is,

- What the different types of cybersquatting are, and

- How to prevent cybersquatting.

What Is Cybersquatting? A Cybersquatting Definition

Cybersquatting, also known as domain squatting, is the practice of registering a domain name that resembles a well-known organization or person without their authorization. Domain registrant buys the domain in bad faith, typically with the goal of making a profit from the person or organization’s goodwill or causing reputational harm to them.

So, how are cybersquatting cases handled? The answer depends largely on your location. The Anti-Cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA) is applicable for the cybersquatting cases in the U.S. and Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP) for the international disputes.

There are three main components of cybersquatting definition.

1. The Domain Name Is Identical or Confusingly Similar to A Registered Trademark

But what is considered to be an identical or confusing similar domain? There’s no fixed definition of “confusingly similar” as it’s a pretty subjective term. Generally, court or arbitration committee decides whether a domain in question can confuse or deceive people on case-by-case basis.

Another part of this point is “registered trademark.” A person or company can seek legal remedy only after registering its brand as a trademark.

If the business/person is already famous but before they register the trademark, if someone else buys the domain with an intention to sell it to the brand owner in the future at a premium price, it also falls into cybersquatting.

For an example of how a cybersquatting case can play out, check out the Wayne Rooney case.

2. The Domain Is Obtained in Bad Faith

While dealing with a cybersquatting case, courts also consider the intension of the domain registrant. If the cybersquatter’s intention is one or more of the following, it’s included in bad faith’s definition:

- Sell the domain to the original trademark owner at a premium price.

- Attract traffic on the website to earn money from advertisements or affiliate marketing.

- Use the cybersquatted domain to spread malware or run phishing scams

- Sell domain name to the competitors.

- Ruin a person or company’s reputation.

- Show disagreement with the original site’s cause or mission.

- Start a similar business and leverage the established brand’s goodwill to deceive their customers.

3. The Registrant Has No Apparent or Legitimate Interest in the Domain Name

Sometimes people unintentionally end up buying domain names that resemble famous businesses or celebrities. Some words look unique or abstract in one language but are popular and trademark in other language.

For example, locolo.app is a startup in Estonia for renting products while locolo.in is an online grocery delivery platform in India. In the same way, in the U.S., Princeton.edu represents New Jersey’s Princeton University. But in India, Princeton.in represents a club!

Although both businesses in each scenario share the same domain name with different top-level domains (TLDs), they are otherwise entirely unrelated and don’t have any intention to capitalize on their counterparts’ reputations. Such examples are considered as having a genuine interest in the domains because they have established businesses or organizations using the names.

Now that we know what cybersquatting is in a general sense, let’s explore the eight different types of cyberquatting.

Types of Cybersquatting

1. Typosquatting

Typosquatting is one of the most common types of cybersquatting. In this situation, the cybersquatter intentionally buys misspelled domain names of popular brands. The goal is to create an illegitimate website that people will land on when they make a typing error (i.e., misspell or hit one or more wrong keys when typing a domain name.

Typosquatting involves adding or omitting any numbers, letters or periods in the original spelling of a domain. It also includes swapping the order of letters or words in a domain as well. Basically, typosquatting includes any such spelling variant that people might mistype.

For example:

- Twiitter.com,

- Twittr.com,

- Twittor.com,

- Twitter.cm, and

- wwwtwitter.com (omitting the period between “www” and “twitter”).

When popular sites have millions of visitors, even if a small fraction of people make a typo, the typosquatters receive lots of free traffic on their illegitimate websites.

2. TLDs Exploitation Cybersquatting

Top-level domains (TLDs) are the last part of a domain name like .com, .ca, .tech, .org, and more. There are more than 2,000 TLDs available in the market. Although big companies like Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, etc. keep a large portfolio of such domains, it’s not feasible for small and medium-sized businesses to buy the domain names containing their brand name in all the TLD variants.

Cybersquatters exploit this situation and buy matching domains of a popular business with different TLDs. Cybersquatters make an inappropriate site using such a misspelled domain and coerce the business owners to buy the domain at a premium price to protect their brands’ reputations. Some cybersquatters make phishing sites using such domains to mislead the original site’s customers.

3. Gripe Sites Cybersquatting

Not all cybersquatters are out to make a profit — some have other agendas. Some people take the path of cybersquatting to:

- Ruin a business/person’s reputation,

- Take personal revenge,

- Publish their extremist political, religious, or social beliefs, or

- Mock or make a satire on the original site’s values or mission.

They post content on such cybersquatting websites that contradict the original site’s values or put it in an embarrassing situation.

Examples: microsoftsucks.com (To show hatred for Microsoft) and GodHatesFigs.com (parody of GodHatesFags.com). To see more, be sure to check out our article on cybersquatting examples.

Although a rare practice, some businesses buy the “typo-domains” of their competitors and make an inappropriate website or write stuff that is harmful to the competitor brand’s image and redirect traffic to their own website.

4. Look-Alike Domain Cybersquatting

Cybersquatters buy similar-looking domain names of original brands by adding special characters, numbers, or common words in it. Sometimes they interchange the words if the domain name is long.

Let’s look at a few examples of these methods of cybersquatting:

- Adding extra characters: Amazon-site.com, Amazonshopping.com, Amazon-official.com, Amazon1.com, Amaz0n.com, Ama-zon.com, Microsofty.com,

- Reordering the words: guardianthe.com (instead of theguardian.com), retailnotme.com (instead of retailmenot.com), businessfox.com (instead of foxbusiness.com), and newsfox.com (instead of foxnews.com)

5. Misleading Subdomain Cybersquatting

Attackers sometimes split a domain name into two parts, buy a domain of the latter part and add a subdomain of the former part. Not sure what we mean? Let’s consider a quick example with the domain www.britannica.com.

In this scenario, the original domain is www.britannica.com. If a typosquatter divides it into two parts — let’s say, britan and nica —they buy a domain named nica.com and make a subdomain britan.nica.com to try to trick people.

Cybersquatters also buy random domain names and make subdomains containing famous brand names. For example, amazon.randomsite.com or facebook.anydomain.com.

Non-tech savvy people might not be aware of the fact that virtually anyone can make a subdomain of any word (or number). It is the primary domain that is written before TLD (.com, .in, .org, .edu, etc.) that represents the legitimacy of the domain name.

So, in the case of facebook.anydomain.com, the Facebook word is used just as a subdomain and that doesn’t represent the legitimacy of the primary domain. The primary domain is anydomain.com. In other words, you can’t buy facebook.com, but you might be able to buy any other available domain name and make subdomain using “Facebook” word.

6. Celebrity Name Cybersquatting

Cybersquatters buy domains of celebrities’ names before the celebrities themselves decide to do so. If celebrities already have websites, perpetrators buy similar or close-matching domain names. They attract traffic by misleading fans and make revenue through third-party advertising or selling merchandise embedded with a celebrity’s brand name/images.

Often, cybersquatters make phishing sites and lure fans to share their personally identifiable information (PII) like email addresses, phone numbers, dates of birth, or even their physical addresses. Some cybersquatters’ goals are to sell such domain names to the celebrity at a premium rate.

Celebrities like Paris Hilton, Madonna, and Jennifer Lopez have been victims of cybersquatting in the past.

7. Expiration Date Exploitation Cybersquatting

Some cybersquatters keep an eye on target domain names and their expiration dates. If the domain owner fails to renew the domain name, the perpetrators grab the opportunity and register the domain in their names.

Thankfully, the likelihood of such renewal failures to occur for big companies is rare because they typically receive a couple of reminders before the domains’ expiration dates. However, it still does happen. But this scenario typically affects startups and small companies. This could be because the businesses’ founders are:

- In an indecisive stage,

- Deciding whether to continue their businesses, or,

- May have temporary halted their businesses for another reason.

Whenever the company owners decide to restart their businesses, if cybersquatting occurs, they are forced to buy back their domains from cybersquatters at premium rates.

8. Homograph Attacks

This next type of cybersquatting is incredibly malicious. In homograph attacks, cybercriminals use punycode (a subset of Unicode characters) to convert regular domain names (which traditionally consist of ASCII numbers, letters, and special characters) into domain names that visually look legitimate. So, in this type of attack, bad actors intentionally create domains using punycode that you can’t distinguish visually from real website domains.

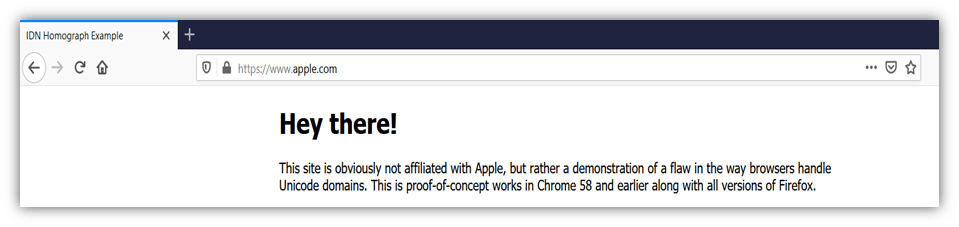

Xudong Zheng shows how he was able to buy a domain that looks like “apple.com” by using punycode. He bought the domain “xn--80ak6aa92e.com,” which appears virtually identical to “apple.com” in the URL bar.

Pretty scary, right? Thankfully, Chrome and Internet Explorer now have security mechanisms that detect homographic domains. But if you click on this link and open it with Firefox or Chrome 58 (or earlier), you can still see the fake apple.com website. Here’s a screenshot of the example below:

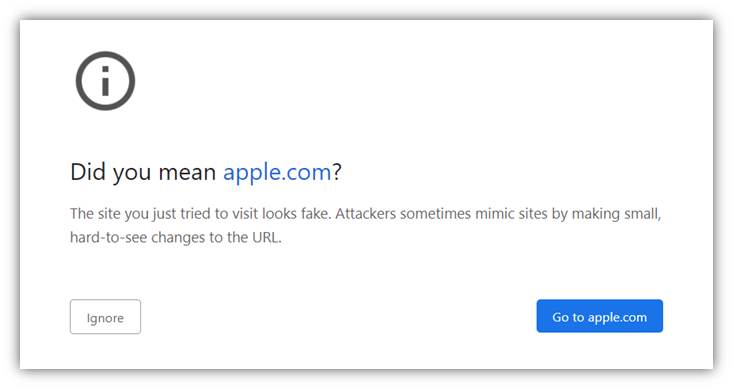

But since Chrome had addressed this issue, this is the message you’ll now see on later versions of their browser:

How to Prevent Cybersquatting of Your Domain (Or Accidentally Visiting One)

This section is broken down into two sets of topics depending on whether you’re a site owner or a site visitor. The first set of tips is for business owners indicating how to prevent cybersquatting; the other set of precautionary tips is for website visitors who find themselves on a cybersquatting website.

How to Prevent Cybersquatting: A Business Owner’s Guide

1. Know Your Legal Options

These are some laws that can protect you if you have become a victim of cybersquatting:

- Anti-Cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA):This act has an elaborate definition of cybersquatting and what factors should be considered at the time of the dispute. If the domain registrant is found guilty of cybersquatting, the court can order the forfeiture, cancelation, or transfer (to the complainant) of the domain in dispute. Note: This law is applicable in the U.S. only. If the domain registrant resides in a different country, ACPA won’t be able to intervene.

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO): For international disputes, WIPO facilitates the arbitration and mediation service where an expert panel reviews the case and resolves the conflict. They take into the consideration the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP), which was developed by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN).

2. Register Your Business’s Trademark as Soon as Possible

In both the ACPA and UDRP, the protection extends to trademark owners only. If you haven’t registered your personal name or brand name as a trademark — or worst, if someone else registers it before you — these regulations won’t be able to help you. Hence, it’s crucial to register your trademark ASAP to get protection from regulatory bodies.

3. Make a Small Investment By Buying Your Domain with Other Prominent TLDs

It’s obvious that you’re not going to buy 2,000+ domains with different TLDs. But at least buy the domains with the prominent TLDs like .com, .net, .org, .biz, etc. You can also buy domains that closely match to your brand name. If you’re planning to have a business in different countries, buy those country-specific domains like .ca, .in, .co.uk, .au, etc. ASAP. You can redirect these domains to your main site later on.

Domain names will cost you around $10/year (for non-specialized names). While the cost is minimal in the grand scheme, taking this step can save you from a long (and costly) legal battle in the future.

4. Communicate with the Cybersquatting Domain Owner

A we mentioned earlier, sometimes the domain registrant’s intention is not cybersquatting and it can be a pure coincidence that they bought the domain that matches your brand name. So, before going to court and spending thousands of dollars in legal proceedings, you first may want to try to communicate with the domain owner directly.

Sometimes, they might be ready to hand you over the domain for a small price, which might not be a financial burden for you. So, you may want to consider communicating with the person to see if you can come to an agreement with them. This may help you to avoid becoming a victim of a reverse-cybersquatting complaint or attract controversies like Microsoft and their Mike Rowe situation. But, again, we first recommend that you check with a legal professional to see what all of your options are.

Cybersquatting Prevention for Website Visitors

Cybersquatting is a battle between con artists and domain owners, and there’s not much you can do to avoid falling prey to it except being vigilant. With this in mind, we’ve outlined a few steps you can follow to ensure you don’t find yourself on one of those phony look-alike sites:

1. Double-Check the Spelling of the Website to Avoid Typosquatting

Before inputting your login credentials, PII, or financial information, develop a habit of checking the address bar to verify the domain’s spelling and to make sure you’re on the right site.

2. Keep an Eye on the Website’s Appearance

Trust your gut. If something feels kind of fishy, be cautious because you may be on a cybersquatting site. If you see one or more of the following “symptoms” on a site, be alert.

- Too many pop-ups and advertisements.

- Misleading “download” or “buy” buttons.

- Frequent redirects to unknown sites.

- Automatic downloads.

3. Look For the Padlock Sign

If you visit a popular site and you see “not secure” in front of a domain name or there’s no padlock icon, be cautious. These are two signs that you may be on a fake site. Reputable and genuine websites always install an SSL/TLS certificate on their website and there’s a padlock sign before their domain name. This padlock means that data is transmitted between your browser and the site’s server via a secure, encrypted connection.

Pro tip: Be sure to check the site’s SSL/TLS certificate information to see if the site is using a legitimate certificate and if it contains any organizational information. This will help you to determine whether a website is legitimate. Otherwise, with being able to verify the organization’s identity, you don’t know who’s on the other end of that encrypted connection.

Wrapping Up on Cybersquatting

Before deciding a business/brand name, most entrepreneurs check whether the domain name of their desired brand is available in the market. They also check whether any domain names are already registered that match their proposed business name.

However, for an existing business, it’s not easy or feasible to simply start fresh with a new brand name. If you find any domain that appears to be infringing your copyright or trademark, and if the domain registrar’s intentions seem fishy, you might be a victim of cybersquatting. You’ll want to speak to a legal professional to find out what your options are in this situation.

(65 votes, average: 4.62 out of 5)

(65 votes, average: 4.62 out of 5)

2018 Top 100 Ecommerce Retailers Benchmark Study

in Web Security5 Ridiculous (But Real) Reasons IoT Security is Critical

in IoTComodo CA is now Sectigo: FAQs

in SectigoStore8 Crucial Tips To Secure Your WordPress Website

in WordPress SecurityWhat is Always on SSL (AOSSL) and Why Do All Websites Need It?

in Encryption Web SecurityHow to Install SSL Certificates on WordPress: The Ultimate Migration Guide

in Encryption Web Security WordPress SecurityThe 7 Biggest Data Breaches of All Time

in Web SecurityHashing vs Encryption — The Big Players of the Cyber Security World

in EncryptionHow to Tell If a Website is Legit in 10 Easy Steps

in Web SecurityWhat Is OWASP? What Are the OWASP Top 10 Vulnerabilities?

in Web Security